Welcome!

The Allure of Fashionable Fur

A Boom in the Sealskin Market

Until the 1820s, no significant market existed for fur seals in Europe or the United States; nearly all skins went to Canton, China. Limited use in the United States and Europe included caps, gloves, carriage rugs, trunk covers, and “beaver” hats. Between 1825 and 1870, improved processing, especially in dyeing and guard hair removal, enhanced the quality of pelts. London enterprises handled nearly all fur seal skins by 1870 when fashion began to drive up prices. People now prized seal fur for coats, muffs, and trim. An average pelt sold for less than $5 in the late 1860s and for $40 by 1900. Pribylov seals ranked second-best in quality to those of the South Shetland Islands - Cape Horn. Another, smaller population of southern fur seals bred at the Lobos Islands off Uruguay.

Schooner captains from Victoria began trading for fur in the 1850s. Commercial pelagic sealing, or the taking of fur seals at sea, began off the British Columbia coast in 1866 and achieved the status of an industry by 1879 as fashion boosted the value of seal pelts. Because of this, a widely accepted concept evolved that the conservation of any renewable resource consists in its wise management and use for the benefit for men and women - and on a basis of sustained or increasing yield. This definition has endured in the case of the Alaska fur seal which has provided the world with one of its most valued and beautiful furs.

Immediately after the purchase of Alaska by the U. S., a number of independent companies began sealing operations on the Pribylov Islands, taking about 300,000 skins the first season. An act of Congress on July 27, 1868, prohibited the killing of fur seals and on March 3, 1869 the islands were set aside by the U.S. Government as a special reservation for the protection of the animals. The following year, the U.S. Treasury Department was authorized to lease exclusive rights to take seals on the islands, with the stipulation that no females were to be taken. Further legislation in 1874 authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to establish catch quotas and open seasons for the lessee.

The ACC’s 20-Year Lease Begins

Under the first 20-year lease, beginning in 1870, the Alaska Commercial Company took 1,977,377 sealskins. A second 20-year lease, to the North American Company, produced only 342,651 sealskins for the period ending in 1909. The leasing system was discontinued in 1910, and since then, the Alaska fur-seal has been under the management of the Federal Government, first by the Secretary of Commerce through the former Bureau of Fisheries, and now by the Secretary of the Interior through the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. The net proceeds from the sale of sealskins have since then been paid into the U.S. Treasury. Total sealskin sales alone have amounted to many times as much as the purchase of Alaska for $7, 200, 000 in 1867.

All the Alaska Commercial Company’s sealskins from the Pribylov Islands were shipped to San Francisco, the skins discharged on the dock from the steamers, and counted out under the supervision of Treasury officials. They were packed on the dock, with a liberal allowance of salt, in specially built barrels or casks, and then shipped by railroad, ultimately arriving in London. The sealskins, as well as other varieties of furs, were received by C. M. Lampson & Co, London, to be put up for sale at public auction. Many foreign buyers who were unable to go to London to attend the auctions, appointed Lampson & Co. as purchasing agents for the same furs they were selling, knowing that both parties would be treated honorably. Alfred Fraser, a partner of Lampson in London and who had offices in New York City, was also the Alaska Commercial Company representative in that city. During the four decades from 1870 to 1910, the seal skins were shipped to London for dyeing, then imported back into the United States, paying a tariff duty. Once Americans learned the art of dyeing sealskins, this enabled most of the business to be done in this country. The fur of the sealskin is gray when obtained but is dyed in different colors. One of these colors, bois be cambeche, was fancied by Mrs. Herbert Hoover, who as “First Lady” sent ten dyed Alaskan sealskins to Princess Marie José́ of Belgium, on the occasion of the latter’s marriage to Prince Umberto of Italy.

The Threat of Pelagic Sealing

Pelagic sealing began to develop on a commercial scale about 1879. This resulted in the indiscriminate killing of the seals regardless of age or sex by fishermen of various countries, bringing the great Bering Sea herd of Alaska fur seals dangerously close to extinction. From 1879 to 1909, many of the seals shot or speared in the open sea were not recovered. Because females comprised 60 to 80 percent of the pelagic catch, the effect on the Alaska herd was disastrous. Prompted by the US, on July 7, 1911, Great Britain, Japan, and Russia concluded a convention for the protection of the fur seals of the North Pacific. Pelagic sealing was prohibited except by the indigenous population who used their traditional weapons. The resulting Pelagic Treaty provided for the first time a basis for the sound management of the North Pacific fur seals. On February 9, 1957, a new interim North Pacific Fur-Seal Convention was concluded by Canada, Japan, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and the United States similar in form to the 1911 convention, providing international protection and a rational management program for the Alaska fur-seal herd. The new convention stipulated that Canada and Japan each would receive 15 percent of the sealskins taken commercially by the U.S. and by the U.S.S.R. The herd was able to increase steadily until its numbers reached the carrying capacity of the breeding grounds on the Pribylov Islands. There has been, during all but a few of these years, a steady harvest of surplus animals. The result has been a revenue that in total exceeds by more than ten times the price paid to Russia in 1867 for the entire territory of Alaska.

3d Scans

Click and drag on the items below to see each item in detail.

Seal fur golves

Seal fur hat

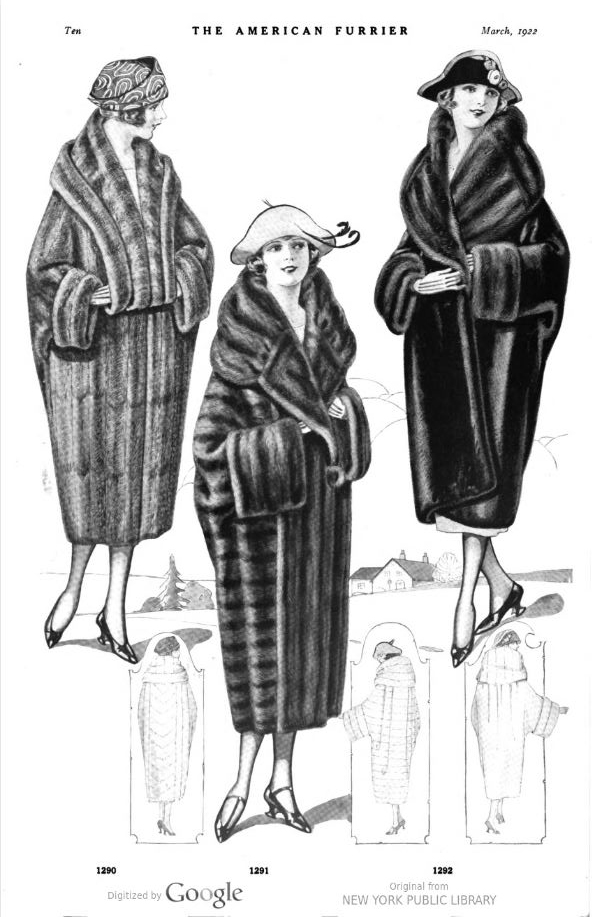

Seal fur coat

Fouke Fur Co. of St. Louis

Ever since the beginning of that sound and scientific management program, the Fouke Fur Company of St. Louis had the good fortune to play an important part in it. As the they explain in their booklet, The Romance of the Alaska Fur Seal, “For it is at Fouke Fur Company…that the skins of the Alaska seal go through the long and intricate procedure of processing which turns them into one of the world’s most desired furs…It is a far cry from…raw pelts to the beautifully finished Alaska Fur Seal skins which are sold for the Government at the Semi-annual auctions in the Foukes Sales Rooms. When one compares the skins side-by-side, however, it is readily possible to appreciate the technical skill and long experience necessary to carry out the more than 125 processing operations which bring about the transformation – as well as the three months which must elapse between raw pelt and finished skins.”

“The guard hair is first extracted, exposing the soft, silky under-fur. The density of this under-fur has been determined, by the aid of the microscope, to be approximately 300,000 fibers to the square inch. The pelts are dressed by a type of chamois tanning, which produces unusual pliability, softness, and strength. Alaska Fur Seal is finished in four different processes; one, ‘SAFARI,’ the effect of which is a rich dark brown; two, ‘MATARA,’ which results in a more neutral brown with an overtone of bluish grey; three, ‘KITOVI,’ which gives a dark grey with bluish overtones; and a fourth process which produces a new, lustrous black. In the natural state, the under-fur is dull and curly, but through the Fouke Process, the fur is permanently de-kinked, leaving a gleaming luster and evenness of pile … Seal [fur] of today is so much lighter in weight and so much more supple than in our grandmothers’ time that no proper comparison can be made.”

Touting its expertise, the company marketed its Alaska furs to the world, “Today, the leading couturiers and designers of New York, Paris, Rome, London, and other fashion centers throughout the world are utilizing the grace and suppleness of this fur in many fresh and interesting ways. Fouke-Processed Alaska Fur Seal, long a prestige leader of the fine fur family, is most conspicuous in fashion news of the season’s openings, and women of all over the world have been quick to take notice of its outstanding style postion and real worth.” (Romance of the Alaska Fur Seal. Fouke Fur Co, 1958.)

Courtesy of Suzanne Werkema

Fur Seal Hat, ca. late 1800s - early 1900s

Note: Ms. Werkema’s great-grandfather, the hat's owner, was Jewish. His surname was Grossman, and he came to the Pittsburgh area from Russian-controlled Poland around the 1880s. He worked as a peddler until he became a haberdasher and opened a men's clothing store.

Fouke Fur Co. and the U. S. Government

From 1913 on, Fouke Fur Co. of St. Louis represented the U. S. Government in the processing and sale of its Alaska sealskins continuously for 35 years. The same company also was an agent for the Canadian government, the government of the Union of South Africa, as well as numerous large, private, licensed shippers. It specialized in the processing and sale of fur sealskins; only one other concern processed fur sealskins, C. S. Lampson & Co. in London. Still, St. Louis was considered the fur sealskin market of the world. There were a number of fur-receiving houses and fur dealers with furs coming from various states as well as every province in Canada. The first public auction sale of furs ever held in the U. S. took place on Dec. 16, 1913, in St. Louis when the U. S. government decided to sell its sealskins at public auction in the U. S. instead of allowing them to be shipped to the London market.

In the mid-1940s, St. Louis sealskin auctions recorded the largest attendance ever assembled, attracting 250 to 300 foreign and domestic buyers at each sale (compared to as few as 25 to 60 bidders during the Depression). After price controls were lifted, government annual gross revenues soared to $3 to $4 million in the last four years of the decade. By 1948, the Pribilof seal herd had been restored to 3,837,131 animals, capable of supplying an annual average of more than 50,000 skins for auction. In 1962, the Fouke Fur Co. moved all its operations from St. Louis to Greenville, South Carolina; they continued to process and sell sealskins there until the company was dissolved in the mid-1980s.